sm

smCOLUMN SIXTY-SIX, DECEMBER 1, 2001

(Copyright © 2001 Al Aronowitz)

SECTION ONE

PAGE TWO

sm

sm

COLUMN

SIXTY-SIX, DECEMBER 1, 2001

(Copyright © 2001 Al Aronowitz)

PART TWO:

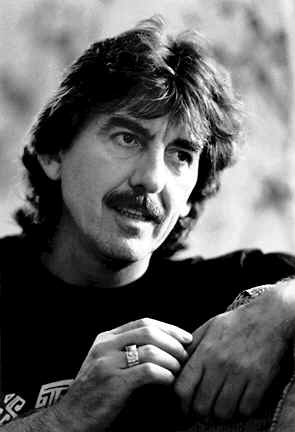

GEORGE AT THE BOBFEST

GEORGE HARRISON

(Photo By Myles Aronowitz)

George

Harrison had told me to meet him at the Pierre at 4 p.m. but it must have been

close to 5 when a charming, dark-haired woman assistant whose name I think was

Linda found me downstairs in the Pierre Cafe, just off the lobby, where I was

with my photographer son, Myles, having a cup of coffee at my table in

anticipation of the long night ahead. In

my all too wasted past, I would have equipped myself with stimulants much more

exotic and illicit than coffee, but that great self-destructive binge of

creativity spawned by the 1960s had long ago come to an emphatic end, no matter

to what extent its fruits might be celebrated later tonight.

Tonight would

be when George would mount the stage of Madison Square Garden to join a

veritable Who's Who of Rock's most accomplished heroes in a "Bobfest,"

which is what Neil Young would call it when it came his turn to step up to the

mike. What's a "Bobfest?"

"'COLUMBIA

RECORDS CELEBRATES THE MUSIC OF BOB DYLAN' HONORS HIS 30TH YEAR;" the

headline on the press release said. "ALL-STAR

OCT. 16 MADISON SQUARE GARDEN CONCERT EVENT SELLS OUT IN RECORD 70

MINUTES." I think the last

Garden show to sell out that fast was George's Concert for Bangladesh.

I don't know. I've been out

of the loop for the last 20 years. Except

that the tickets for this show started at $80 and went up to $150 and you were

allowed to buy only one pair at a time.

The cast for

tonight's show included a house band consisting of Booker T. on keyboards, Steve

Cropper and G. E. Smith wielding guitars, Duck Dunn on bass and Jim Keltner on

drums. I told George I still had my

"Jim Keltner Fan Club" pin that George had made up on one of his

previous tours years ago. For this

show, George ordered a supply of black T-shirts that bore a line from one of

Bob's songs, in crazy, colorful lettering:

"It's

That Million-Dollar Bash."

The show

certainly had a million-dollar cast. The

lineup featured Eric Clapton, Kris Kristofferson, John Mellencamp, Willie

Nelson, Tom Petty, Johnny Cash and June Carter, Tracy Chapman and on and on and

on, including Roger McGuinn, whose Byrds got their first hit with a pop version

of Dylan's "Mr. Tambourine Man."

In an article

in the Times two days before the concert, Peter Watrous quoted Roger as saying

that if Dylan hadn't come along, pop music might have stayed strictly

"bubblegum" and there might not have been Bob's brand of

"thinking man's music."

"All

those concepts of his might have been lost," Roger was quoted as saying.

"The Beatles were doing straight pop, and Dylan had a talk with

Lennon and after that the Beatles changed, got motivated to do something more

interesting, more intellectual."

Which is exactly the reason why I decided it was so essential for me to get Bob and the Beatles together in the first place. Well, it wasn't exactly like acting as go-between for the Arabs and the Jews, but I knew that such a meeting was going to be an earth-shaking

At

first, Dylan was

lukewarm

to meeting the Beatles

event.

I wrote about Dylan and Lennon as mirror images of each other.

To me, it was obvious that if I could get Dylan and the Beatles together,

what would evolve is exactly what did evolve.

They influenced one another and everybody's music got better still.

The world benefited.

It's true

that I had youthful ambitions of one day claiming far greater contributions to

contemporary culture than that, but I certainly feel honored to have played at

least that role. At first, Dylan

was lukewarm to meeting the Beatles. He

sneered at their music as kid stuff. To

Bob, the Beatles were more "bubblegum." Bob had started out as a rock-and-roller like all the other

kids, but when I met him he was in his folkie-purist phase. He turned up his nose at pop, but I argued:

"Today's

pop is tomorrow's folk music."

I finally got

Bob and the Beatles to meet in Manhattan's Hotel Delmonico. Afterwards, when the Beatles were playing a benefit at the

old Paramount Theater in Times Square, I brought Bob to the show.

He stood on a chair in the wings to watch.

He was staying a lot at my house in Berkeley Heights, N.J., in those days

and afterwards he asked my wife to drive him over to Rondo Music on Route 22 in

Hillside. There, he rented an

electric guitar and took it back to my house.

Soon, he was in the studio recording his first electric album.

"It's

chaos, absolute chaos down there at the Garden!" George told me when Linda,

after apologizing profusely for her boss' lateness, finally ushered me into the

sitting room of his suite. "I

don't know how they're ever going to get that show together.

I'm sorry I had to keep you waiting but they kept me waiting.

Then I still didn't even get to do my run-through."

He smiled and

we shook hands and then we hugged. We

hadn't seen each other in close to 20 years.

I reminded him that the last time was in his suite at the Plaza after his

last Garden concert.

"That

was in '74," George recalled. "We

used to come to New York a lot when [Allen] Klein managed Apple.

Then he no longer managed Apple and we no longer came to New York so

much. I've only been here probably

two or three times in 20 years since John was shot.

Actually twice. The [Rock

and Roll] Hall of Fame in February, '88 and then '89 or '90 to do a couple of

tracks on Eric's [Clapton] 'Journeyman' album."

I asked

George what he thought about New York nowadays.

"I think

they should pull a lot of it down and plant some trees in it," he laughed,

"and thin out the people a bit. Ship

a few people off into different places. I don't think it's very healthy at all. It's crumbling, it's tired, but it still has a kind of

atmosphere. In the '60s and '70s

for me, it was kind of interesting when we used to hang out, we used to go in

weird places.

"Then

there's that kind of thing where you can get into feelin,' 'Hey, man, yeah,

we're in the city and this is city life and we're cool.' But for me, I have no desire to be in any city, even a small

city. I don't like cities.

I want to be as close to nature as possible.

Purely just because I want to survive and I think it takes its toll on

you---the pollution, the noise, the uptightness, the hostility---and all it does

is it fries your nervous system and knocks years off your life."

I asked

George what he has been doing to advance his musical career.

"Musically,

I've just sort of come along," he said, but then he quickly added:

"Not really. . . Like I'm

doing it like most people who are doing their career, making sure they have an

album out every year and the tours and all that.

When I feel like it, I'll just do an album.

I'll probably make one. That's

what I've been planning to do the last couple of months is to start writing some

new tunes. . .

What about

the Traveling Wilburys, I asked, referring to the fictional group that George

concocted with the help of Dylan, Petty and ex-ELO leader Jeff Lynne.

"The Wilburys was fun," George said. "I think we should do some more again, because it is relatively simple. It's not like a solo album, in which the responsibility is on you. You can hide behind each other's backs and maybe write lyrics that you maybe wouldn't write

George

also

had become

a movie mogul

on your own.

I thought that was fun. I

like that last album we did. The

first one, we did in 10 days, to write it and do the basic tracks, and then Jeff

Lynne and I spent a bit more time with Tom puttin' it together.

"The

last one, the second one we did, it took six weeks to write it, record it and

mix it, everything. It's really

good because you tend to get bogged down doin' solo albums.

You get used to doin' it over and over until you lose the point.

So, it's a little rough bug. It's

got that more natural feeling."

Since I last

saw George, he also had become a movie mogul, producing a string of films that

won critical and commercial success.

"When

the economy went bad in the world," George said, "a lot of people

couldn't pay us what they owed us and we suffered a little bit over the past few

years, paying interest on bank loans that were due to the bank from the money

that the other people hadn't paid us. Now

we had to sue Cannon Films. Then

Cannon sold the company to this Italian, Paretti, who was even worse than Cannon

and then he got rid of it to MGM. You

know that big story that was in the papers about Credit Lyonnais. It ended up we won the case and we got the money from MGM,

but it wasn't MGM's fault.

"The

people who actually caused all the problems in the first place got away with it,

really. But they'll get theirs,

eventually. A lot of people in

film, well, in any business, are like that, where they take the attitude, 'We

just won't pay and they won't sue us!' We

just had a few years of trying to regroup and we've got a few projects that

we're trying to get started. I'd

like to do just a few more projects and then see how it goes.

"We

would change the way we do the business because in the past we raised our own

money from the banks. But I think

now the days of those smaller budgeted films which we were making---there's no

market for them. It's just becoming

difficult. So, we've been making

films with Hollywood, with those people. Did

you ever see any of the films we made? Did

you ever see Life with Brian" That

was the first film we did. There

were a few that were quite good. One

with Bob Hoskins. Bought this film

that was being shelved. Good

Friday. One of his first

films."

The telephone

rang and George picked it up. It

was a friend of Tom Petty who cracks backs.

George didn't tell me if the friend actually was a chiropractor or not.

"Where

are you?" George said, talking on the telephone. "I don't think I have time.

Today has just been a mess. I

have so many things to do that I'm just gonna spend some time before I come back

just tryin' to get myself calmed down and have a shower and do all that.

If I get time, maybe I. . . I think it might be best to pass. . . I am a

bit tight around the neck, but I wouldn't worry about it.

If I see you backstage, you'll understand. . .

Maybe you'll be able to fix my neck or something."

George

explained to me that the friend had done George's back the night before but his

back probably had just snapped right back to where it had been before the friend

had cracked it. Anyway, George said

he had found his salvation in guess what? Transcendental

Meditation. Remember the Maharishi?

"It's

quite good to get an amount of stress out," George said. "Today it's a bit odd because I've been doing a lot of

this meditation to gettin' myself together.

I just do it. It's part of

my day, that's the most important thing, twice a day. And today, because my boy came in with some friends of ours

on the Concorde and they came in at 9:30, and we'd. . . so I missed my program

this morning and it's like it feels wrong all day, it's not quite right yet.

"So, I'm

planning, before I go down to the Garden. . .

I'm just going to cool out and do a big long one and get myself

together."

George said

his wife, Olivia, was in the bedroom, where their 14-year-old son, Dhani, was

having a bath.

"But I feel tired as well, for some reason," George said. "Oh, I know why. Because I'm five hours' jet lag, and that's it! I go on at 10:30 tonight, which is like 3:30 in the morning for me, IF the show comes off, because it looked pretty chaotic this afternoon. They were trying to run it down in order to get the timings of everybody. I think they

For

the 'Bobfest,'

they didn't know

when to say no

made a

mistake either by not being able to say no---remember in the '70s when we did

Bangladesh at Madison Square Garden? For me to get the commitment of those people for the basis of

the show, it took quite a while. But

once I knew I had the show, after that, EVERYBODY suddenly wanted to be on the

show.

"We were

getting phone calls, 20 calls a day. All

these different artists who were then volunteering to do it.

But I just said, 'NO! That's

it! We've got the show now!'

Whereas this show, it's like they can't say no.

Or maybe they feel indebted to so many people for one reason or another

or maybe they're just gettin' carried away.

And so consequently, they're paying the price of that right now---by

being three hours behind in the run-through to time the show.

And the show is like three and a half hours long.

I mean I wouldn't personally want to sit in the audience for three and a

half hours, although, at least, it's not just one person to watch.

I mean I don't know anybody I would want to watch for more than two

hours. The best show I've seen in

the last 20 years was a lecture by Deepak Chopra, this doctor I heard, and it

was more entertaining than most rock shows I've seen.

He was talking about the spontaneous fulfillment of desire."

George looked

at me and then looked at the cassette recorder lying on the couch between us as

it wound up every one of his words.

"I would

like to just some time hang out with you, not with that feeling that we're doing

an interview," George said. "Not

that there's nothin? I don't want to say. . ."

All of a

sudden, I was like a cub reporter who couldn't think of the next question to

ask. The truth is that George and

Bob both became suns around which perhaps too much of me had once revolved.

At the concert later that evening, I would find myself weeping with awe

over Dylan's enormous body of work.

"I used

to know these guys!" I felt obliged to explain to the pretty blonde sitting

next to me. She said her name was

Sally and she surprised me by referring to Dylan as "Mumbles,"

affectionately, of course.

"He

always changes the lyrics," she said.

"You can't tell what he's singing anyway."

Later, when

George came onstage, I felt so proud, I turned to Sally and said:

"I was

just talking to him."

"Is he

really as sweet as he looks?" she asked.

"He's a

saint!" I said.

In his Pierre

suite, George said he still had to shower and shave before the 8 o'clock start

of the show, which was now close to two hours away.

He also wanted to know if there were still a Hare Krishna restaurant open

in New York. Myles said all the

ones he knew of were closed.

"They've

got food over at the Garden," George said, "I got them to get some

vegetarian rice and dahl, but now I'm not going to be there to eat it, am I?

I could do with eating. Otherwise,

I'll have no strength at all by the time I get to 10 o'clock.

That's when I'm supposed to go on."

Once, years

ago, George and I went to a Salsa night on East 86th St. Another time, I took

George for his first and last New York subway ride, from Sheridan Square to 14th

St. on the Broadway line. When we

got out at 14th St., cops were chasing someone down the platform with their guns

drawn. But the best night of all

was the night I turned the Beatles on to marijuana. That was the night I brought Bob up to meet them at the

Delmonico Hotel. We all had one of

the best laughs of our lives that night. We

did nothing but laugh at one another. That

was the night that ushered in Pop's Psychedelic Era.

Now, 28 years

later, I no longer smoked anything, but I had scored a chunk of hash in my

pocket for George just in case he needed it.

But George wasn't having any, either.

He started talking about the guy who lives for so long in the country but

then decides to get an apartment in the city.

"He sits

in the dark because he doesn't know how to plug the light," George said.

"In a way, that's what we all do.

That's enlightenment. People

don't really wanna look for enlightenment.

And so, it's like we go through our lives in the dark.

But we can just go inside and plug in the source within you/without you.

Just learn and be able to dip in, that's the thing.

Each time you meditate you can dip in.

Each time you meditate you can dip in to that reservoir.

"I

forgot about it for years and then I got really stressed out during the early

'80s or it was the culmination of all the monkey business I'd been doing.

It took me years trying to figure out what's happening to me?

I think it was just the accumulation of those years when there was drugs

in my life and those years of staying up all night and partying and just being

in recording studios and business problems and all these people I talked about

earlier---the banks wanting their money and these other people not paying us and

all that got me to the point where I said, 'Jesus!

I gotta do something here!"

"And I

remembered, 'What about meditation!' I

had forgotten totally that that's what it was all about---to release the stress

out of your system. And I got back

into that! And I do a double-dose

now and it's like, say, whereas an alcoholic can't go through a day without

going to AA or doing some kind of a program like that, for me, it's the

meditation program. In order to

keep myself focused and keep the buoyancy, the energy, and also to realize that

all this stuff that's going on is just bullshit.

It's hard to be able to not let that get next to ya!"

##

CLICK HERE TO GET TO INDEX OF COLUMN SIXTY-SIX

CLICK HERE TO GET TO INDEX

OF COLUMNS

The

Blacklisted Journalist can be contacted at P.O.Box 964, Elizabeth, NJ 07208-0964

The Blacklisted Journalist's E-Mail Address:

info@blacklistedjournalist.com

![]()

THE BLACKLISTED JOURNALIST IS A SERVICE MARK OF AL ARONOWITZ